“Pray favor us with your narrative,” the man said.

Unless I am very much mistaken, that is the singular voice of the “sleuth-hound, the relentless, keen-witted, ready-handed” Sherlock Holmes, whose methods seem like mental sleight of hand.

But, unveiling his methods may have great benefit. We will here endeavor to lay before you some of the methods that may help us in conjuring the skills of Sherlock Holmes, the master of abductive reasoning.

Holmes was ever eager to parade his mastery: near the beginning of every story, Holmes flashes the prowess of his abductive powers—reasoning from incomplete observations to the simplest, logical explanation. Invariably, he baffles visitors, by identifying their personal history, recent events, travels, and even thoughts simply through observation:

“There is no mystery, my dear madam,” said he, smiling. “The left arm of your jacket is spattered with mud in no less than seven places. The marks are perfectly fresh. There is no vehicle save a dog-cart which throws up mud in that way, and then only when you sit on the left-hand side of the driver.”

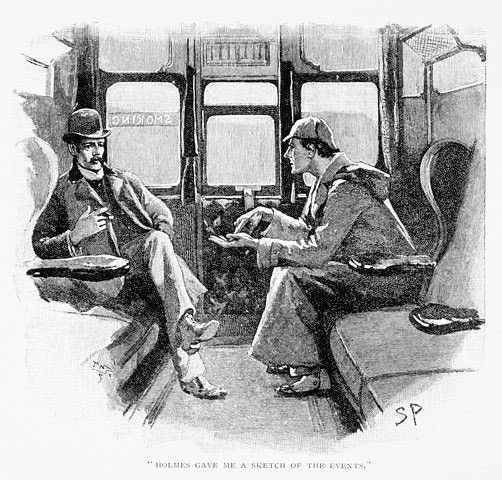

As Dr. Watson says to Holmes:

“When I hear you give your reasons the thing always appears to me to be so ridiculously simple that I could easily do it myself … I am baffled, until you explain your process. And yet I believe that my eyes are as good as yours.”

Watson can see as well as the next man. He even learns the “methods.” But, Holmes remains the undisputed “genius” and Watson the struggling student:

“’Pon my word, Watson, you are coming along wonderfully. You have really done very well indeed. It is true that you missed everything of importance, but you have hit upon the method…

We have a genius, Sherlock Holmes, who pulls back the curtain to reveal his magic, offering us his methods for study. We are as captivated as Watson was. Here’s a guide to what Watson missed:

- Observation

Holmes tells Watson, “Never trust to general impressions, my boy, but concentrate yourself upon details.”

In his unpublished advice to painters, Leonardo Da Vinci directed the painterly eye to observe details in an order, never moving on until the first detail is fixed in the mind’s eye. Like Da Vinci, Holmes fixes on the details of a scene down to a minute scale: the cigar ash, the indentation on a plush sleeve, or the scrape on a shoe—all details apparent to anyone who chooses to observe.

- Analysis

Holmes: “It is of the highest importance in the art of detection to be able to recognize, out of a number of facts, which are incidental and which vital. Otherwise your energy and attention must be dissipated instead of being concentrated.”

Separating the wheat from the chaff in problem solving is never easy. Even Holmes admits to following the wrong scent on occasion. Here, if I’m not much mistaken, Holmes relies on his vast experience to imagine patterns and scenarios which encompass the facts. Upon hearing the details of a new case, he refers to the notes he maintained on his own cases and others. He devoured the many newspapers of 19th century London, which were steeped in the news of crime. So, like the jazz improviser, he could imagine a starting point for his reasoning.

- Empathy

“But I have heard, Mr. Holmes, that you can see deeply into the manifold wickedness of the human heart.”

What a blessing for Mr. Holmes that there be no single human wickedness, but a spreading into multiple branches. He cultivated empathy, the ability to imagine the inner workings of another person’s mind. In his own words: “You know my methods in such cases, Watson. I put myself in the man’s place, and having first gauged his intelligence, I try to imagine how I should myself have proceeded under the same circumstances.”

- Seeing from multiple perspectives

“When he [Holmes] had an unsolved problem upon his mind he would go for days, and even for a week, without rest, turning it over, rearranging his facts, looking at it from every point of view, until he had either fathomed it, or convinced himself that his data were insufficient.”

Problems are like mountains—you cannot move them. Instead, you can only move yourself in relation to the problem. Holmes devoted hours to “rearranging” the facts, turning them over and over in his mind to see them from every possible point of view. Too often, we assume that we have seen the extent of a situation, when, in fact, we have only seen from our own limited perspective. Multiple perspectives enhance problem solving, which is why a CEO must listen to her employees, a teacher must listen to his students, and a politician must listen to all her constituents.

- Confirmation

“I had,” said he, “come to an entirely erroneous conclusion, which shows, my dear Watson, how dangerous it always is to reason from insufficient data… I can only claim the merit that I instantly reconsidered my position…”

A hypothesis can be imagined from incomplete observation, but it is only useful until it is disproved. Holmes, like most scientists, is willing to abandon his reasoning when the facts dictate. Confirmation—or, if you prefer, testing, proof-reading, replication—is imperative to avoid bias, inaccuracy and muddled assumptions.

Should you adopt the methods of Sherlock Holmes? “It’s every man’s business to see that justice is done,” Holmes said.

My dear reader, I can only conclude with words from Holmes himself:

“These are very deep waters… Pray be precise as to details.”